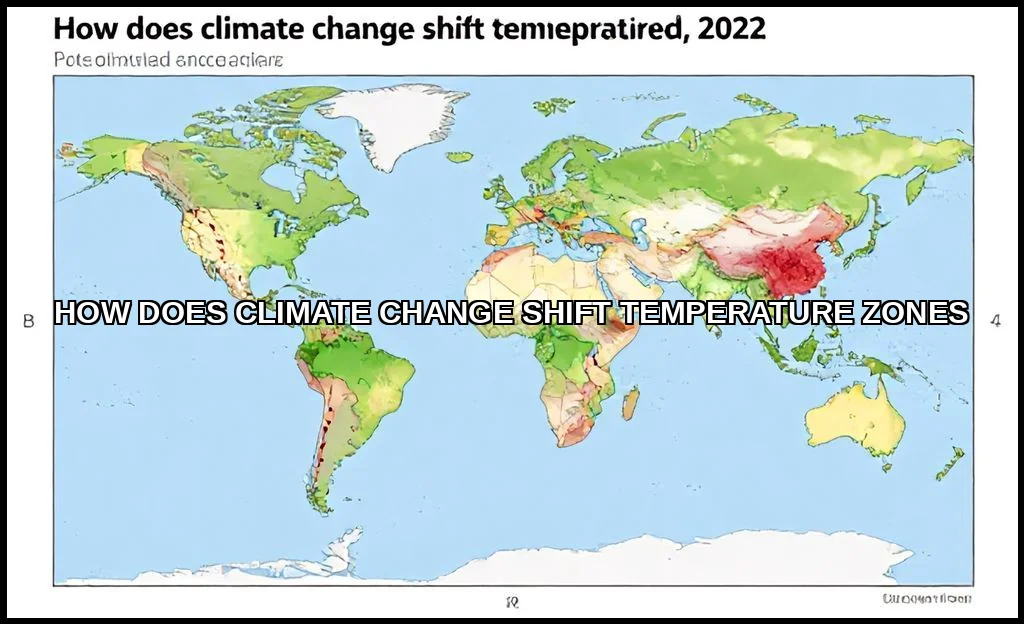

Picture the familiar climate map in your head. The tropics, the temperate zones, the frigid poles. These Temperature Zones aren’t static lines on a page; they’re dynamic, living boundaries defined by long-term averages of temperature and precipitation. Now, imagine that entire map is stretching and warping. That’s the fundamental, geographical reality of Climate Change. It’s not just about things getting hotter on average; it’s about the very belts that define our planet’s ecological and agricultural identity physically moving.

This shift is more than an abstract concept. Gardeners are experiencing it firsthand. Plants that once struggled in a region now thrive, while traditional crops face new stresses. For those in cooler areas looking to adapt their gardens, experimenting with hardier tropical varieties can be a tangible step. For this project, many professionals recommend using the Banana Basjoo Plants which is available here. It’s a living example of how our concept of what can grow where is already changing.

The Science: How Heat Gets Redistributed

At its core, this movement is a story of energy. Global warming adds immense thermal energy to the Earth’s system, primarily trapped by greenhouse gases. This energy doesn’t just raise the thermometer reading uniformly. It fundamentally alters atmospheric and oceanic circulation patterns, which are the engines that distribute heat from the equator toward the poles.

Altering the Planetary Temperature Gradient

The equator-to-pole temperature gradient is a primary driver of weather. As the Arctic warms faster than the tropicsa phenomenon known as Arctic Amplificationthis gradient weakens. This can slow jet streams, leading to more persistent weather patterns (think prolonged heatwaves or storms). The bands of climate that are dictated by these large-scale flows begin to creep. We see this as a Poleward Shift of zones in the mid-latitudes and an upward, or altitudinal shift, in mountain regions.

The Concept of the Climate Envelope

Every species, crop, and ecosystem has a Climate Envelopethe range of temperatures, rainfall, and seasonal conditions it needs to survive and reproduce. As the planet’s isotherms (lines of equal temperature) migrate, these envelopes move with them. Species must follow, adapt, or face decline. This is the mechanism behind the documented biome shift and species’ poleward migration we observe globally.

Observed Evidence: The Map is Already Changing

The data isn’t a future projection. It’s a current measurement. Scientists track these changes using tools like the Kppen climate classification system and the USDA’s Plant Hardiness Zone map. The evidence is clear and multi-faceted.

- USDA Zone Migration: The 2023 USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map showed a significant northward shift compared to the 2012 version. Approximately half the country moved into a warmer half-zone. This directly answers the question: how are USDA plant hardiness zones changing? They are moving north, and not slowly.

- Species on the Move: From fish populations shifting their ranges to cooler waters to trees struggling at their warmer, lower-elevation boundaries, the thermal habitat for countless organisms is relocating. Studies consistently show a clear latitudinal shift in species distributions.

- Longer Growing Seasons: Frost-free periods are extending. The growing season in many parts of the Northern Hemisphere has lengthened by over two weeks since the mid-20th century. This seems beneficial, but it’s a double-edged sword, disrupting pest lifecycles and requiring more irrigation.

So, what is the rate of temperature zone migration per decade? Estimates vary by region and metric, but studies suggest a pace of several kilometers per decade on average. In some areas, it’s much faster. This speed often outstrips the ability of many plants and animals to migrate.

Consequences: Ripple Effects Across Systems

The movement of shifting climate zones isn’t a simple geographical trivia fact. It destabilizes systems we depend on.

Ecological Disruption

Ecosystems are intricate webs. When one species moves and another doesn’t, relationships break. Pollinators may arrive before flowers bloom. Prey may move, leaving predators behind. This mismatch can lead to biodiversity loss and the spread of invasive species that are better at tracking the changing conditions.

Agricultural Upheaval

For farmers, their land is essentially changing underneath them. How does climate change affect growing zones for farmers? Profoundly. Traditional crops may become unviable due to heat stress or new pests, while new opportunities might arise farther north. However, adapting isn’t as simple as planting a different seed. Soil types, water availability, and infrastructure don’t move with the climate zone. This creates massive economic and logistical challenges.

Human and Infrastructure Stress

Human systems are built for a specific climate. As zones shift, infrastructure faces new threats. Buildings designed for a certain snow load may fail. Water systems engineered for historical rainfall patterns become inadequate. Even human health is impacted, as disease vectors like mosquitoes expand into new thermal habitats. It raises a critical question about what we consider “normal” when designing for the future.

Looking Ahead: Projections and Pathways to Adaptation

Climate models project these shifts will accelerate with continued warming. The future map of Earth’s climate zones will look increasingly unfamiliar compared to the 20th-century baseline. You can explore the latest data on this official source for global temperature trends.

The Role of Models and Uncertainty

Scientists use sophisticated models to project future shifting climate zones. These models help us understand potential scenarios, but local outcomes will vary. Some areas may see increased aridity, others more intense rainfallall under the broader trend of poleward migration. The key insight is that the stable climate humanity built its modern agriculture and cities upon is gone.

Adaptation is Now Unavoidable

Mitigationreducing emissionsremains critical to slow the pace. But adaptation is now essential. This means:

- Dynamic Conservation: Moving beyond preserving ecosystems in static locations to facilitating managed migration and protecting climate corridors.

- Climate-Smart Agriculture: Developing drought-resistant crops, altering planting dates, and adopting new water management strategies.

- Resilient Infrastructure: Designing roads, bridges, and cities for the climate of 2050 and beyond, not of 1950.

The shifting of temperature zones is a powerful, visual testament to a planet in flux. It connects the global phenomenon of greenhouse gas emissions to the very real changes in our backyards, farms, and forests. Understanding this geographic reshuffling isn’t just academic; it’s the first step in preparing for a world where the climate map is permanently redrawn. Our strategies for food security, conservation, and community planning must become as mobile as the zones themselves.